This week, Pew Research released survey results that showed significant growth in support for increased funding for local police departments from 2020 to 2021:

The share of adults who say spending on policing in their area should be increased now stands at 47%, up from 31% in June 2020. That includes 21% who say funding for their local police should be increased a lot, up from 11% who said this last summer.

Support for reducing spending on police has fallen significantly: 15% of adults now say spending should be decreased, down from 25% in 2020. And only 6% now advocate decreasing spending a lot, down from 12% who said this last year. At the same time, 37% of adults now say spending on police should stay about the same, down from 42% in 2020.

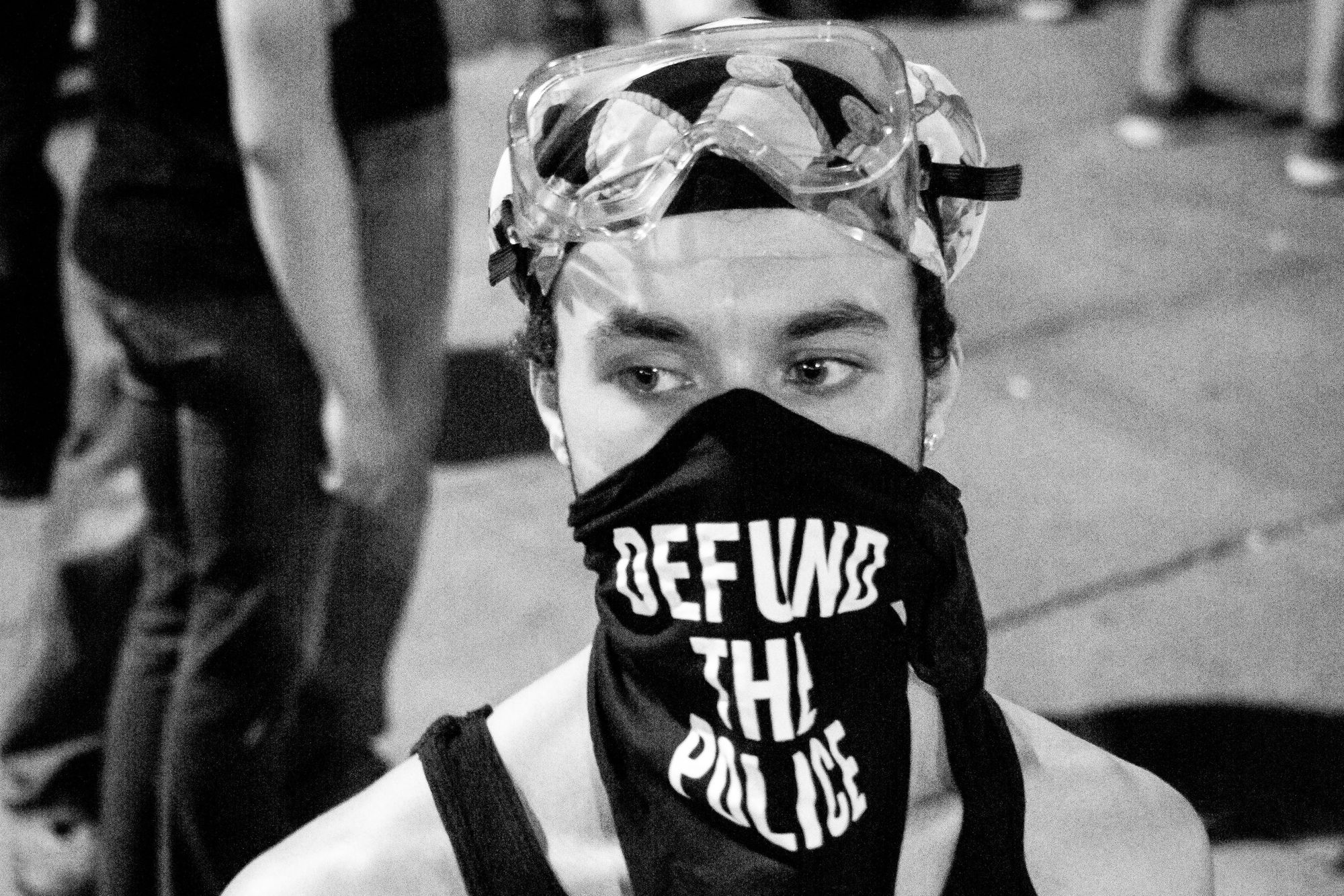

On a macro level, this is not good news for activists and others who have been pushing to “defund” police. That said, data like this should be considered in context and commentators should resist the temptation to confuse politics and policy. If we are to achieve any meaningful reform, there must be some common understanding of the needs and desires of those who have demanded change and the institutions they are demanding change from.

Limits of polling on municipal budgets

It’s unlikely that most people polled are intimately familiar with their own city’s municipal budget and, specifically, how much their city spends on policing, either in real terms or as a percentage of the city’s outlays. Even fewer, I would reckon, know the allocation of funding within a department, such as how much goes to salaries, pensions, overtime, equipment, vehicle maintenance, or training. At a more granular level, I would bet that very few know how their local departments deploy available officers (standard patrol units, traffic, SWAT teams, vice and gang units, homicide, etc.); how those departments and its various units determine enforcement targets or public safety generally, how they try to achieve those goals, and how successful those efforts are; or how money is allocated among the various precincts or service areas within the city. All of which to say: polling about funding, as a policy matter, doesn’t really say much about the effectiveness or efficiency of public money to the police in any given city.

That said, as a political matter, how people respond to the police funding question can be illustrative of how people are feeling. Given the recent nationwide rise in homicides and the general state of anxiety that has accompanied the pandemic, it is not particularly surprising that some people want more support for cops if it means they will feel safer. This isn’t entirely off-base, as visible police presence has been shown to reduce crime in a number of controlled experiments.

At the same time, it is important to note that of the demographics polled, the only groups with a majority of respondents that want to increase police funding are people over 50 years old and people who identify or lean Republican. The majority of the population and most of its subgroups want police funding to stay about the same or be reduced.

While defunding has lost political momentum over the past year, there is still no mandate to increase police funding.

To defund or not to defund?

There are two main problems with the talking discourse around “defunding the police.” First, as mentioned above, funding qua funding doesn’t tell you much about the efficacy of a particular department or its priorities. In almost any other context (save defense spending)—schools, public works, and myriad subsidies of all kinds—Republicans and free-market folks understand that public funding and good results are not necessarily correlated. Yet, when it comes to cops, too few of them interrogate how those departments are spending such vast amounts of public resources.

Second, “Defund!” as a rallying cry can motivate activists in the streets and, with enough public pressure, can get local politicians to take positive actions. But with our politics becoming increasingly nationalized—with local police policy becoming a hot button issue for federal and statewide offices—it’s an electoral liability for reformers, particularly in purple jurisdictions. In the wake of the 2020 elections, in which Democrats lost House seats despite winning the White House, moderate Dems came back to Washington incensed that they had to defend against calls to defund. Positive local policy change can become a political cudgel that can set back reform nationally when Republicans decide to run against defunding just as an idea.

The funny thing is, there is nothing particularly radical about the idea of defunding police absent the current context. Municipal coffers are far more limited in spending power than the federal government. Thus, when activists call for more money for schools, health care, housing, and other non-carceral remedies for underserved communities, the first question they would get from any responsible city official is “Where would we get the money?” Their answer is the police budget. These are the basic tradeoffs in any budget negotiation.

Whether defunding police is a good idea depends on how one goes about it. For example, I am sure that at least a few million dollars of the nearly $2 billion allocated to the Chicago Police Department could be spent more efficiently in ways that help the most underserved communities. In a vacuum, I don’t think most people (besides the department and its unions) would blink an eye at that. But people get caught up in and turned off by Black Lives Matter politics—or are entrenched defending police prerogatives—so smart policy goes out the window. As I’ve advocated in my own city, reassigning officers from harassing, arrest-centric units in Black neighborhoods and putting them back on patrol to ease staffing shortages can kill two birds with one stone, and doing so would be budget neutral. But the people at opposite ends of these fights—the activists and the cops—are yelling past each other, sometimes literally, and so we’re all losing sight of shared goals.

Thinking critically about change

As we consider ways to improve policing, for both communities and the officers who serve in them, we need to look beyond political phrases and the divisive politics that go with them.

At the national level, most generalist talking heads on either side make sweeping generalizations about police and policing as if it is a singular entity with one way of doing things, rather than a decentralized conglomeration of policy, culture, politics, and procedure implemented by thousands of agencies and countless subdivisions with varying levels of competence and accountability. Most of the commentary at this level obscures far more than it illuminates, except to the extent it reveals the preferred macropolitics of the given writer or speaker.

At the local level, activists too often paper over the fact police remain popular with a majority of the local and national electorates, while police and their supporters downplay the legitimate and serious complaints of the activists. The activists know the truth in Frederick Douglass’s statement, “Power concedes nothing without a demand,” and so they speak boldly and stridently about what they want, sometimes irrespective of political realities—and with defensible justification. Police and their supporters, in response, circle the wagons and bitterly defend themselves as if their entire way of life is at stake. Whether they admit it or not, the police have the majority of the public on their side, and so they can (and do) protect the status quo against calls for significant change. Both sides are playing the hands they’ve been dealt.

What can be responsibly said generally is that laws and local politicians often provide terrible incentives for officers, and then blame the cops when things go wrong, leading to further police insularity and entrenchment. Meaningful reforms will require changing the way police do their jobs and providing the proper structures for them to succeed. At the same time, the most underserved communities need more support that may or may not involve the police.