This week, the New York Times published an interactive feature on the mental health toll of police violence felt by Black Americans. From the article:

It’s hard to measure the individual toll these events take on mental health. The New York Times dispatched reporters in more than 20 U.S. cities to interview 110 Black people, across generations and socioeconomic groups, about how acts of police violence affect them. The Times also commissioned Morning Consult, a polling company, to survey Black adults in the United States about what they feel, and how they cope, when they learn that a police officer has hurt or killed a Black person.

While more than half of respondents reported feeling ongoing sadness, anger and fear about police violence, the survey also found that Black people feel more safe than unsafe when they see a police officer. (As the numbers below illustrate, a portion also report feeling anxious when they see an officer.)

Many people The Times interviewed shared personal experiences of excessive force and harassment by the police; others talked about well-known cases — like those of Rodney King and Eric Garner — from years ago.

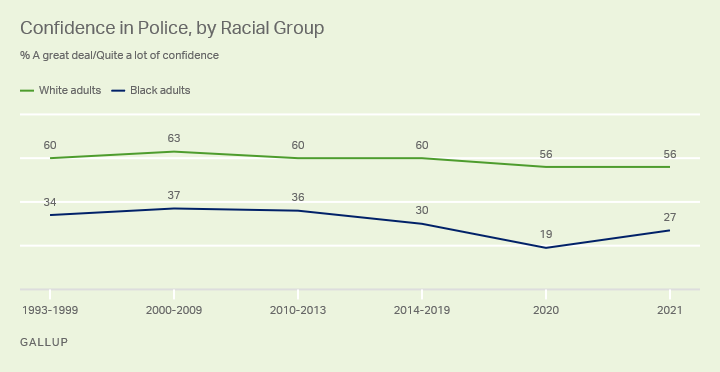

A matter of trust

There’s a lot to unpack in the piece, but the first thing to recognize is that simple, one-sided narratives of either pro- or anti-cop sentiment do not reflect the reality of how people view the police. Views, feelings, and opinions varyand are not necessarily binary (i.e., entirely good or bad). That different people have different feelings may seem obvious, but the inartful phrase “Black people feel more safe than unsafe when they see a police officer” will almost invariably be used against someone who discusses the relative lack of Black Americans’ trust or confidence in the police, which is simultaneously true.

How police shape how they are perceived

Implicit in both the Times article and the Gallup poll summary, national news events can have significant effects on the public perception of police. Officers are right to think this is a little unfair because there are roughly 18,000 distinct law enforcement agencies in the United States and what an officer does in Staten Island or Cleveland has no direct connection to officers in Denver or San Diego. That said, years of Gallup data show that such headline-grabbing incidents tend not to have long-lasting effects on public trust over time, so while unions and other police defenders may blame “the media” for negative police perceptions, there are other reasons for the persistent trust gaps over so many decades.

Because Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely to have involuntary police contacts, be subjected to a search of their person or vehicle, and experience police use of force or the threat of force, the reports of those actions reverberate through social and family networks. Data continually show that young Black men in particular experience pretextual pedestrian and traffic stops—that is, a stop for a minor violation under pretext so an officer may initiate a warrantless criminal investigation on the sidewalk or roadside—and that they resent it. A policy of antagonistic and investigatory police contacts will naturally undermine trust among those who experience or hear about these incidents from friends and loved ones. (For a more in-depth analysis of how negative perceptions of traffic stops throughout drivers’ social networks, see Pulled Over: How Police Stops Define Race and Citizenship, by Charles R. Epp, Steven Maynard-Moody, and Donald P. Haider-Markel (University of Chicago Press, 2014)).

Finding a real balance between safety and security

While some will argue that these stops are conducted for public safety, Yale Law School professor and President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing member Tracey Meares explains why that isn’t good enough:

[P]eople's conclusions regarding their assessments of the fairness of legal actors, institutions, and law does not flow from their assessments of police effectiveness regarding tasks such as crime reduction or apprehension of wrongdoers. People tend to place much more weight on how authorities exercise power as opposed to the ends for which that power is exercised...

It is imperative that policing agencies recognize that crime reduction is not self-justifying. Police action taken for the purpose of making communities safer, especially aggressive police action, can have the counter-productive result of destroying the very reservoir of trust on which communities and policing agencies depend for a proper functioning system. So the idea promoted by folks like Raymond Kelly, Rudy Giuliani, and former Mayor Michael Bloomberg that we ought to somehow balance the benefits that groups of people such as African Americans receive from plummeted crime rates without truly acknowledging and understanding the costs to them in terms of enforcement—and here I am not just talking of incarceration—shortsighted and deeply, deeply flawed.

As I laid out in my law review article, Thin Blue Lies: How Pretextual Stops Undermine Police Legitimacy, officers’ frequent use of investigatory stops to search for crimes they have no legal justification to suspect delegitimizes those stops and, by extension, the police as an institution. While some people who lose trust in police as a direct or indirect result of an aggressive police stop still call the police, many do not. In these and other respects, police can be their own worst enemy because they cannot rely on the cooperation of the community they need to do their jobs effectively.

Meares’ larger point is even more salient: American communities want safety and security. Unfortunately, many American police departments offer neither. As Jill Leovy wrote in the Wall Street Journal:

Today’s controversial policing tactics are part of a law enforcement model in which prevention is everything and vigorous response an afterthought. Officers are better at stopping people at random than at tracking down those who do real harm; they are better at arrest sweeps than at investigating major crimes.

This dilemma should be at the heart of American policing reform conversations: officers try to improve public safety but violate the security of the people they are supposed to protect. Communities want to be safe from criminal elements but they also want to be secure from the government overreach inherent in aggressive police stops and searches, which is supposed to be a constitutional right. Recall the language of the Fourth Amendment:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Surely police can find other ways to reduce violent crime than intrusive and humiliating roadside searches that rarely result in serious contraband seizures. As a legal matter, Supreme Court precedent allows police to go on fishing expeditions to look for evidence of crime, the text and spirit of the Fourth Amendment notwithstanding. But as a policy matter, police departments should seriously reevaluate this and other invasive practices that cost more in their own social capital than they produce in public safety.

The New York Times piece is a story about mental health, but it is also a profound indictment showing how insecure many Black Americans feel about the officers charged with protecting them. The onus to repair this fundamentally broken trust falls squarely on police brass and city officials who task officers to carry out these and other self-defeating tactics that sow mistrust in the communities that need quality policing the most.