Debating how to fix Medicare is a long-standing tradition in Washington. But with the exception of reforms to reduce Medicare drug spending through the Inflation Reduction Act, leaders in both parties have largely ignored entitlement reform, including critical changes to preserve Medicare’s long-term finances. Particularly distressing is that Republican leaders, including the party’s presumptive nominee for president in 2024, are turning away from the party’s historical commitment to fiscal restraint and instead committed to leave Medicare alone.

Medicare’s fiscal crisis is well documented. Medicare’s trust fund, which finances the program’s hospital benefit, is predicted to run out of money by 2031 with subsequent steep cuts to providers to follow. And as the number of workers paying taxes to fund Medicare benefits decreases in relation to the number of Medicare enrollees, the program’s contribution to deficits and debt continue to grow, at a time when interest on the national debt is skyrocketing due to high interest rates.

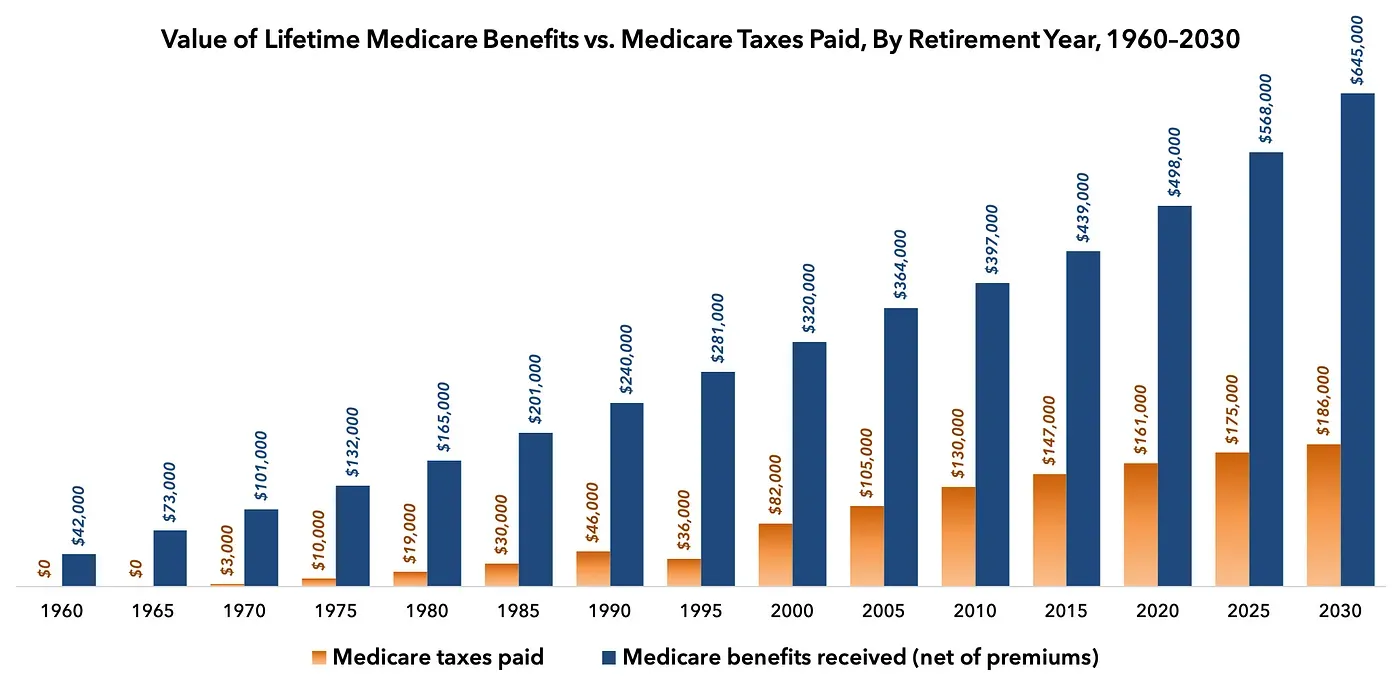

Medicare has become a massive—and growing—transfer of resources from younger workers to older retirees. And since the elderly are no longer the poorest Americans—on the contrary, Americans over the age of 65 are now significantly wealthier than younger Americans—Medicare is largely a transfer of resources from poorer to wealthier individuals.

The long-term financial picture for Medicare needs securing reform now. For this reason, it is refreshing that a cadre of free-market thinkers—led by the Heritage Foundation’s Robert E. Moffit, and former White House official Marie Fishpaw—published a plan to counter the do-nothing crowd inside the Beltway. Modernizing Medicare: Harnessing the Power of Consumer Choice and Market Competition, is a compilation of essays aimed at reforming Medicare’s broken financing model. The book’s reforms mirror many of the ideas we’ve discussed at FREOPP and positions Medicare to better meet the needs of current seniors while placing the vital program on a fiscally sustainable path for generations to come.

The premise of the book is familiar to policy wonks, but is nonetheless a departure from what most voters think of as “Medicare reform.” Rather than implementing benefit cuts to make the program solvent, Modernizing Medicare argues for transitioning Medicare’s 1960s fee-for-service model to “a model where dollars follow patients in the form of ‘premium support,’ a defined contribution system that allows beneficiaries to direct their government subsidies to plans of their choosing.”

Modernizing Medicare makes its case for broader Medicare reform by offering a path through the political minefield. It seems obvious Medicare is fiscally unsustainable and one of the key drivers of America’s debt and deficit problems. It is also clear to any honest observer that the program’s financial protection for seniors is under threat. But the book addresses the political problems of Medicare reform by offering solutions that save money while preserving or improving Medicare’s slate of benefits.

To make the argument, the book’s opening essays describe Medicare’s past and present, focusing primarily on the weaknesses of traditional Medicare in contrast to the strengths of Medicare Advantage, the program’s private insurance option. As evidence of its superiority, Christopher Pope of the Manhattan Institute notes that Medicare Advantage enrollees experience lower rates of hospital admission and lower rates of expensive and ineffective medical procedures in the last few months of life. In addition, the book cites research that shows Medicare Advantage costs ten percent less than traditional Medicare after using differences in mortality to control for other unobserved differences in health status. In addition, after controlling for health status, demographics, and geography, Medicare Advantage enrollees experienced 20-25 percent fewer hospitalizations and made 25-35 percent fewer emergency room visits.

It would be understandable if the authors set out a reform agenda that would slowly dismantle the traditional Medicare program with the hopes of scrapping it entirely. But true to the book’s spirit of embracing competition to drive better health care results and prices, Joseph Antos of the American Enterprise Institute also offers ways to reform traditional Medicare to compete better with Medicare Advantage.

The book offers one solution as a bridge to the broader Medicare reform the contributors seek: automatically enrolling new beneficiaries into Medicare Advantage. In doing so, Brian J. Miller and Gail R. Wilensky argue beneficiaries would gain greater financial protection and supplemental benefits. In return, policymakers would gain greater control over the program’s budget as it shifts plan and formulary design to the private market. With incentives properly aligned, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services can focus on innovative plan designs rather than perpetuating its role as an intrusive price-setter that rewards volume over value.

Importantly, Miller and Wilensky address many criticisms of auto-enrollment. Though they present auto-enrollment for company retirement plans as a notable example of the power of such a policy, they acknowledge that the need for health benefits is unique, personal, and more difficult to predict than for retirement planning. Still, the book offers several ways to maximize the positive effects of auto-enrollment while ensuring health insurance plans do not game the system.

Opponents of private-sector health insurance will likely criticize the book’s effusive praise of Medicare Advantage and the proposal to leverage it under a premium support model. A major criticism of Medicare Advantage is that the program’s design, which pays health plans a higher amount of money for enrollees who are sicker, encourages health plans to code for as many health conditions as possible to increase the per-person payment. Some researchers claim these and other “overpayments” result in a slightly higher cost per enrollee than traditional Medicare, despite claims that Medicare Advantage enrollees are healthier at baseline than traditional enrollees.

Thus, the final third of the book is crucial to reforming Medicare Advantage so that it could serve as the backbone of the book’s primary Medicare reform: transitioning Medicare to a premium support insurance program. It includes a chapter on risk adjustment written by Heritage’s Edmund F. Haislmaier that appears quite technical, but deserves close attention by readers.

Risk adjustment exists in Medicare Advantage today, in that insurers are given additional payments if their pool of insureds is sicker and costlier than expected. The current scheme is vulnerable to gaming by insurance companies, leading to insurers seeking healthier enrollees while simultaneously presenting such enrollees to be as unhealthy as possible. A carefully designed risk adjustment system must be the cornerstone of any successful Medicare reform employing premium support so that plans compete for patients based on quality and price rather than seeking the healthiest enrollees.

Though the book offers a solid blueprint for ensuring Medicare’s fiscal sustainability, it leaves some pressing affordability issues unaddressed. Though health plan competition is vital to lowering the overall cost to Medicare, the cost of health plans largely reflects the high underlying cost of American health care itself. A premium support model provides powerful mechanisms to push health care prices in the right direction, but only if policymakers also address the lack of competition in health care provider markets, particularly hospitals and prescription drugs.

For instance, former White House advisor Doug Badger rightly identifies Medicare’s convoluted cost sharing for the prescription drug benefit as a source of higher drug prices because it disincentivizes both drug companies and health plans to negotiate for more rebates. However, the book ignores the rapidly escalating cost of physician-administered drugs paid under Part B, in which doctors are paid a percentage of the drug’s private market price and are therefore incentivized to prescribe higher-priced drugs. More importantly, the existing statute virtually requires Medicare to cover all FDA-approved drugs, regardless of value. Medicare also prevents health plans from excluding drugs of certain disease classes—including very expensive cancer drugs—even when some of these drugs have little to no clinical effectiveness to justify higher prices. Implementing curated drug formularies for all drugs, including physician-administered infusion drugs, would drive additional savings as it does with commercial private insurance.

Additionally, Medicare policy encourages hospitals to aggressively acquire physician practices so that it can bill hospital reimbursement rates for services normally performed in an office setting. “Site neutral” payment reform to end this unfair billing practice enjoys significant bipartisan support, but the book does not address it.

That said, Modernizing Medicare makes its case for broader Medicare reform by offering a path through the political minefield. It seems obvious Medicare is fiscally unsustainable and one of the key drivers of America’s debt and deficit problems. It is also clear to any honest observer that the program’s financial protection for seniors is under threat. But the book addresses the political problems of Medicare reform by offering solutions that save money while preserving or improving Medicare’s slate of benefits. This is crucial because, as health economist Mark V. Pauly points out early in the book, voters will reject any proposal that they perceive reduces their benefits, no matter how much it could help the country fiscally.

But Modernizing Medicare reminds us that Medicare reform need not be a zero-sum game. By implementing premium support within Medicare Advantage, Medicare can provide better coverage and benefits for enrollees while also reducing federal health care spending as a beneficial byproduct.