Sometimes, the slow pace of government bureaucracy means standing in line for two hours at the DMV. Other times, it can throw an entire college admissions season into pandemonium.

At the end of 2020, Congress passed the FAFSA Simplification Act, a longtime priority of now-retired Senator Lamar Alexander (R., Tenn.). The goal of the act was to simplify the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), a form that college students seeking federal grant or loan money must submit. The act directed the U.S. Department of Education (ED) to pare down the overlong FAFSA document from over 100 questions to as few as 18. It also simplified the formula used to determine students’ aid awards, which should result in as many as 1.5 million additional students qualifying for the maximum federal Pell Grant.

The FAFSA Simplification Act and subsequent amendments directed ED to have the new form ready for the 2024–25 academic year. The Biden administration, which took office mere weeks after the act passed, had three years to develop and test the new FAFSA before its official debut.

The FAFSA fiasco

But the form’s launch at the end of December 2023 was a fiasco. Already three months behind schedule—normally the FAFSA is available October 1—ED kept the updated form open for as little as 30 minutes per day. Students reported constant glitches and lockouts. Experts called the form “practically unusable.” In one particularly egregious error, ED neglected to account for inflation in aid eligibility formulas, underestimating student aid by nearly $2 billion.

Though the form is now open 24 hours a day, at least 16 remaining issues keep the process from going smoothly for students. Often these issues require students to completely restart their FAFSA form and, in some cases, students are not able to submit the form at all until ED fixes the issue. Students can call for help, but some have reported hold times of up to three hours.

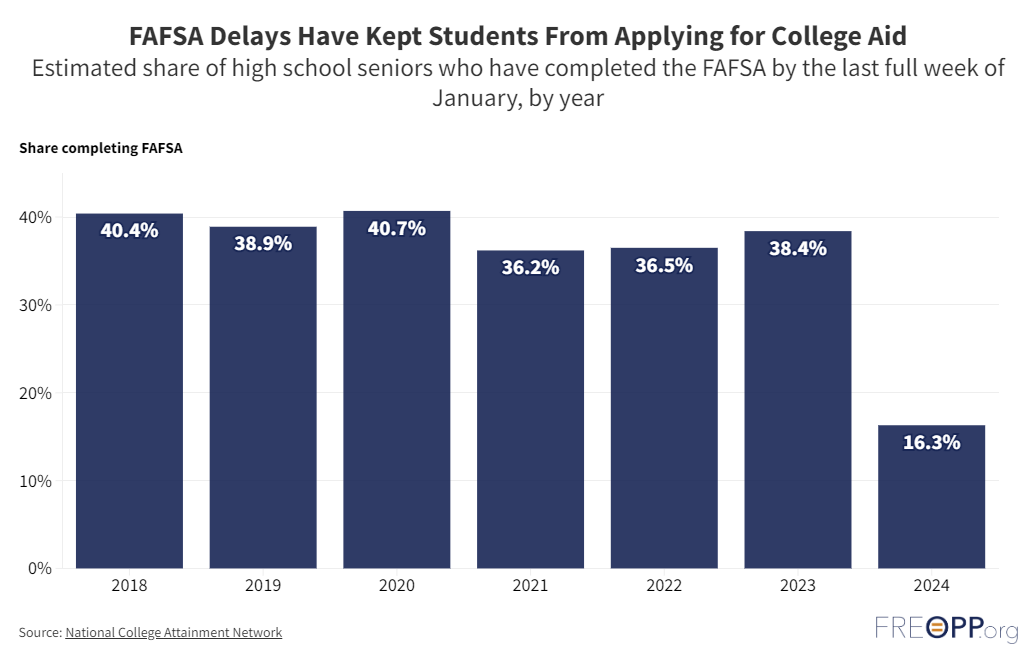

The result of all this chaos: far fewer students have completed the FAFSA than would be expected given past patterns, according to the National College Attainment Network. In a normal year, between 36 percent and 41 percent of high school seniors submit their FAFSA by the end of January. This year, the figure stands at 16 percent.

While those numbers may eventually catch up to previous years, it’s also possible that many frustrated students will simply give up. Those students may try to attend college without federal aid, or skip college entirely.

Delayed financial aid decisions

The latest twist in this saga was ED’s announcement that it will not send students’ FAFSA data to colleges until March. Financial aid experts think this will delay the date schools can send financial aid offers to students until April; and that’s assuming ED can deliver on its promise to send the data next month.

Some colleges are pushing back their admissions calendars to accommodate the delay. But others are maintaining the traditional “college decision day” of May 1. This means some students could have just days to compare financial aid offers from different schools and make their decisions. Negotiating a financial aid package with the school is sure to become much harder.

ED has tried to speed up the process by making financial aid experts available to colleges to help them turn FAFSA data into aid offers faster. It’s also giving away $50 million to nonprofits—such as the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators—hoping they can help colleges too. All this may or may not work to accelerate the process on colleges’ end. But ED’s changes do nothing to ensure students can access and submit the new FAFSA without issues.

What went wrong?

At the request of Republican lawmakers, the Government Accountability Office has opened a probe into the FAFSA launch. This may eventually provide some answers as to what went so disastrously wrong. But it’s reasonable to suppose that other initiatives that ED undertook without congressional direction—including the ill-fated 2022 attempt to forgive student debt, the $300 billion overhaul of loan repayment plans, and myriad regulations targeting for-profit colleges—siphoned away staff and resources that could have been directed toward the new FAFSA.

Such limited capability is all the more reason for federal agencies to stick to the core functions that Congress has authorized them to perform. ED’s adventure into partisan policymaking may come at the cost of timely financial aid decisions for millions of college students. This debacle is an object lesson for the next time a president considers implementing education policy by administrative fiat.